Fractals have been on my mind lately. A fractal, according to Merriam-Webster, is “any of various extremely irregular curves or shapes for which any suitably chosen part is similar in shape to a given larger or smaller part when magnified or reduced to the same size.”

That’s a fairly obscure and technical definition. An example helps. One of the better-known fractals is the Sierpiński triangle, which is created by taking an equilateral triangle and then repeatedly dividing it into smaller triangles:

Because this application of triangles can be done at smaller and smaller levels, you can zoom in or out as much as you want - even infinitely. It’s a rather mesmerizing (or at least dizzying) effect.

Fractals aren’t just a mathematical curiosity, though. For example, they show up in nature, “in such places as broccoli, snowflakes, feet of geckos, frost crystals, … lightning bolts,” and the circulatory system (Wikipedia). Tree branches are one example: the trunk splits into boughs, which split into smaller branches, and so on down to twigs, with (often) a similar branching pattern each step of the way.

Ukraine has been on my mind lately. News stories regularly try to sum up the current state of suffering: As of Tuesday morning, 401 civilians confirmed dead and 801 confirmed injured, with the actual casualties likely much higher. More than 2 million refugees. But that’s just the big picture. Like a fractal, you can zoom in to see more and more detail, and more and more suffering. A wedding with military fatigues and rocket-propelled grenades. Reports of a girl, trapped in rubble, dying of dehydration. Photos of farewells at train stations as the war separates families. A man digging through the rubble of his house after his wife and daughter were killed.

Or you can follow a different branch of the fractal tree to look at Russia: 140 million people in an economy that’s cratered under crippling sanctions, a government that may be about to default on its debts, thousands of Russian soldiers killed, under a regime so repressive that merely calling what’s happening in Ukraine an “invasion” can be punishable by up to three years in prison. All for a war that none of them had any real say in.

Let’s zoom out a step. Here’s a map of the Russian invasion of Ukraine as of this week, courtesy of The Washington Post.

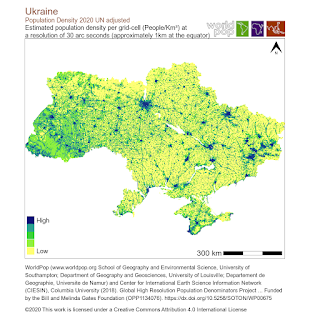

Ukraine’s population is (was) 43 million people. Plenty of those 43 million people live outside of the red areas.

I don’t know how the demographics break down - how many of the casualties and refugees are from different parts of the country - but, given that Putin’s aim appears to be to take all of Ukraine, it’s easy to fear that things could get much worse.

Let’s zoom out again. Here’s Moldova.

It’s another former member of the Soviet Union, just south of Ukraine, small and (like Ukraine) relatively poor. Moldovans worry that their country will be invaded next, especially after Belorusian dictator and Russian ally Alexander Lukashenko showed a map that appeared to indicate planned troop movements into Moldova. Moldova has its own separatist region, Transnistria, similar to Ukraine’s separatist, Russian-friendly regions of Donetsk and Luhansk. Transnistria is tiny (500,000 people), completely outside of Moldovan control, and backwater:

It’s a place of Lenin statues, hammer-and-sickle flags and once-grand Soviet architecture in decay… Unrecognized by the United Nations, it has a currency, the ruble, that is virtually worthless outside its borders. International bank cards don’t work at Transnistrian ATMs. Salaries are low. For all of Russia’s influence, the biggest power in Transnistria is a monopolistic company, Sheriff, that operates with scant oversight and controls everything from the gas stations to the supermarkets to the soccer club.

Anywhere along the fractal, it seems, we can see more loss, more fear, more scars from the past. And that’s just from looking at current events in and around Ukraine. We can follow the branches back through history, to look at the Russian poverty and malaise after the collapse of the Soviet Union that fueled Putin’s rise to power, or the history of autocracy, imperialism, and politicized religion that Putin has inherited. Or we can zoom out further and follow the fractal’s boughs to the civil war in Ethiopia between Tigray and the central government, with “ethnically motivated killings, sexual violence on a massive scale, looting, and mass displacement to unequipped neighbor states and countries”; or the civil war in Yemen, where Saudi Arabia, using US-provided weaponry, is waging a brutal war against Houthi rebels that’s killed over 100,000 people and started a famine that’s killed 85,000 more.

And, of course, if you follow the branches and boughs back far enough, you come to the Fall, to humanity’s rebellion against God that started in Eden and ripples throughout history and throughout the world.

What’s a Christian to do? Or, to be more direct, what is God doing? Our typical answer is that Jesus’ death and resurrection means we can escape all of this and go to Heaven. And that’s true, good, and wonderful, but it’s only part of the story. After all, it would seem strange if God saw this infinite fractal of pain, loss, and death and gave only a single, unitary response. Instead, I believe, God’s redemption and its outworking are similarly fractal, being rooted in Christ’s death, burial, and resurrection but branching out into every aspect of our existence:

- God at work in the thousands of blessings of everyday life - good meals and sunrises and jokes with friends and a sound night’s sleep

- God at work in the arcs of our individual lives, guiding us as we live and work and learn and grow

- God at work in the local church, where we share in the love and support of our brothers and sisters as we worship and serve

- God at work in society, as believers and non-believers alike work under God’s common grace to treat poverty and illness, address injustice, and otherwise ameliorate the effects of the Fall

- God at work through his Word, speaking to us today just as he spoke to its human authors, and speaking to us through the millions of lesser words of Christian preachers, speakers, authors, singers, songwriters, theologians, and journalists who use their gifts to build us up

- God at work even in our hardships, as our hardships help us to develop endurance, character, and hope (Rom 5:4); provide an opportunity to show our faith and gentleness (1 Pe 3:13-16); and inspire others (as Ukrainians’ courage is inspiring many around the world)

- God at work throughout history, as his church spreads the gospel “throughout the whole inhabited earth as a testimony to all the nations” (Mt 24:14)

- God at work through Jesus, who exactly reveals God to us, and whom we can know and relate to as surely as the disciples who walked on earth with him 2,000 years ago

- God at work through the promise of a new heaven and a new earth, where the Fall is not merely escaped but destroyed, where “he will live among us, and we will be his people, and God himself will be with us, and he will wipe away every tear from our eyes, and death will not exist any more—or mourning, or crying, or pain” (Rev. 21:3-4, paraphrased)